Clip

The Passover Haggadah recounts ten plagues that afflicted Egyptian society. In our tradition, Passover is the season in which we imagine our own lives within the story and the story within our lives. Accordingly, we turn our thoughts to the many plagues affecting our society today. Our journey from slavery to redemption is ongoing, demanding the work of our hearts and hands. Here are ten “modern plagues”:

Homelessness

In any given year, about 3.5 million people are likely to experience homelessness, about a third of them children, according to the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty. A recent study by the U.S. Conference of Mayors showed the majority of major cities lack the capacity to shelter those in need and are forced to turn people away. We are reminded time and again in the Torah that the Exodus is a story about a wandering people, once suffering from enslavement, who, through God’s help, eventually find their way to their homeland. As we inherit this story, we affirm our commitment to pursue an end to homelessness.

Hunger

About 49 million Americans experience food insecurity, 16 million of them children. While living in a world blessed with more than enough food to ensure all of God’s children are well nourished, on Passover we declare, “Let all who are hungry come and eat!” These are not empty words, but rather a heartfelt and age-old prayer to end the man-made plague of hunger.

Inequality

Access to affordable housing, quality health care, nutritious food and quality education is far from equal. The disparity between the privileged and the poor is growing, with opportunities for upward mobility still gravely limited. Maimonides taught, “Everyone in the house of Israel is obligated to study Torah, regardless of whether one is rich or poor, physically able or with a physical disability.” Unequal access to basic human needs, based on one’s real or perceived identity, like race, gender or disability, is a plague, antithetical to the inclusive spirit of the Jewish tradition.

Greed

In the Talmud, the sage Ben Zoma asks: “Who is wealthy? One who is happy with one’s lot.” These teachings evidence what we know in our conscience—a human propensity to desire more than we need, to want what is not ours and, at times, to allow this inclination to conquer us, leading to sin. Passover urges us against the plague of greed, toward an attitude of gratitude.

Discrimination and hatred

The Jewish people, as quintessential victims of hatred and discrimination, are especially sensitized to this plague in our own day and age. Today, half a century after the civil rights movement in the United States, we still are far from the actualization of the dream Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. articulated in Washington, D.C., a vision rooted in the message of our prophets. On Passover, we affirm our own identity as the once oppressed, and we refuse to stand idly by amid the plagues of discrimination and hatred.

Silence amid violence

Every year, 4.8 million cases of domestic violence against American women are reported. Each year, more than 108,000 Americans are shot intentionally or unintentionally in murders, assaults, suicides and suicide attempts, accidental shootings and by police intervention. One in five children has seen someone get shot. We do not adequately address violence in our society, including rape, sex trafficking, child abuse, domestic violence and elder abuse, even though it happens every day within our own communities.

Environmental destruction

Humans actively destroy the environment through various forms of pollution, wastefulness, deforestation and widespread apathy toward improving our behaviors and detrimental civic policies. Rabbi Nachman of Brezlav taught, “If you believe you can destroy, you must believe you can repair.” Our precious world is in need of repair, now more than ever.

Stigma of mental illness

One in five Americans experiences mental illness in a given year. Even more alarming, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, nearly two-thirds of people with a diagnosable mental illness do not seek treatment, and minority communities are the least likely to search for or have access to mental health resources. Social stigma toward those with mental illness is a widespread plague. Historically, people with mental health issues have suffered from severe discrimination and brutality, yet our society is increasingly equipped with the knowledge and resources to alleviate the plague of social stigma and offer critical support.

Ignoring refugees

We are living through the worst refugee crisis since the Holocaust. On this day, we remember that “we were foreigners in the land of Egypt,” and God liberated us for a reason: to love the stranger as ourselves. With the memory of generations upon generations of our ancestors living as refugees, we commit ourselves to safely and lovingly opening our hearts and our doors to all peace-loving refugees.

Powerlessness

When faced with these modern plagues, how often do we doubt or question our own ability to make a difference? How often do we feel paralyzed because we do not know what to do to bring about change? How often do we find ourselves powerless to transform the world as it is into the world as we know it should be, overflowing with justice and peace?

Written in collaboration with Rabbi Matthew Soffer of Temple Israel of Boston

Clip

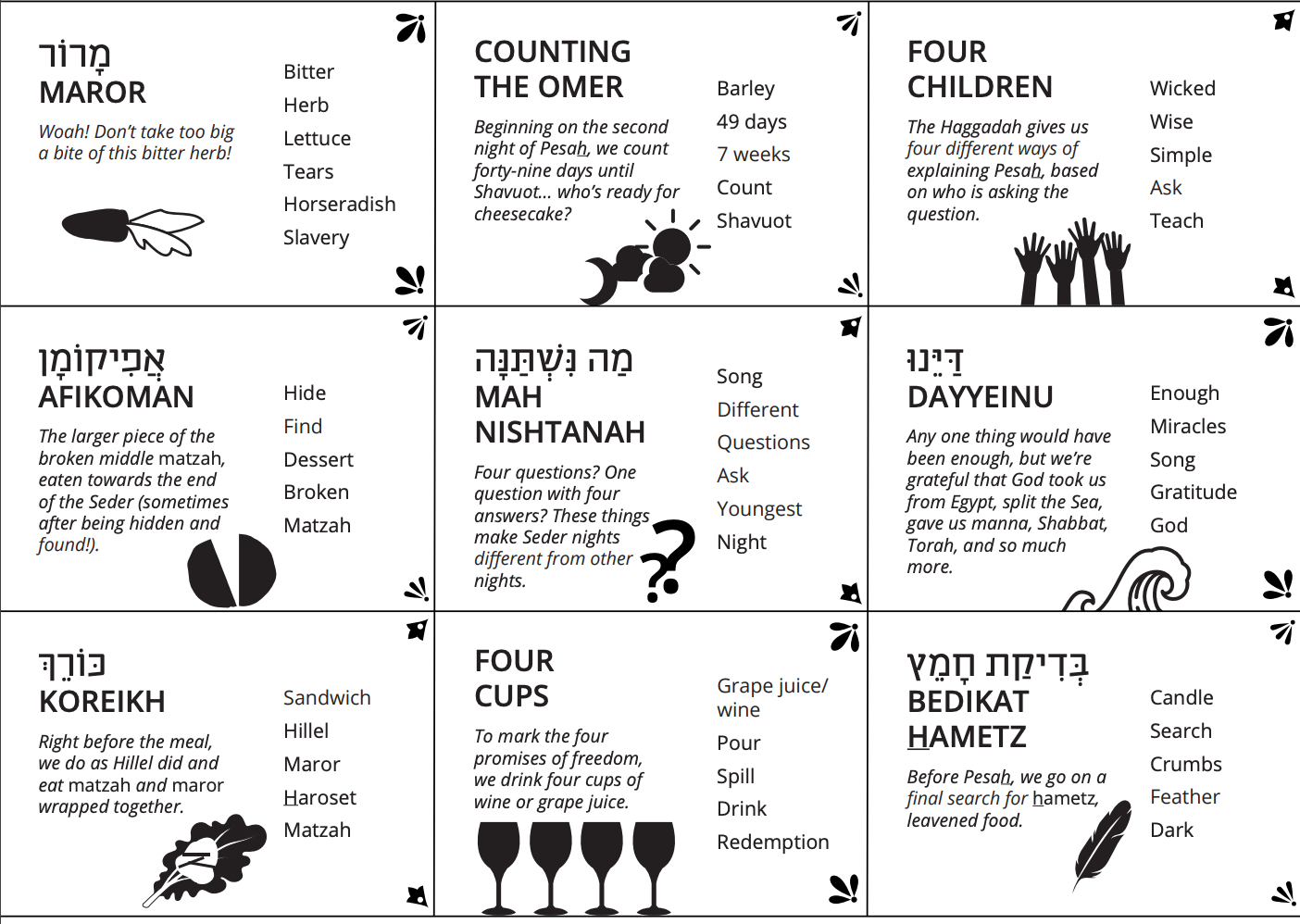

The whole point of the seder is to ask questions. This is your time to ask about things that confuse you, things you don’t understand, or even things you don’t agree with. There really is no is no such thing as a stupid question, especially tonight.

- Joy Levitt (age 16)

Questions are not only welcome during the course of the evening but are vital to tonight’s journey. Our obligation at this seder involves traveling from slavery to freedom, prodding ourselves from apathy to action, encouraging the transformation of silence into speech, and providing a space where all different levels of belief and tradition can co-exist safely. Because leaving Mitzrayim--the narrow places, the places that oppress us—is a personal as well as a communal passage, your participation and thoughts are welcome and encouraged.

We remember that questioning itself is a sign of freedom. The simplest question can have many answers, sometimes complex or contradictory ones, just as life itself is fraught with complexity and contradictions. To see everything as good or bad, matzah or maror, Jewish or Muslim, Jewish or “Gentile”, is to be enslaved to simplicity. Sometimes, a question has no answer. Certainly, we must listen to the question, before answering.

1 / 6